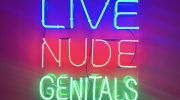

Image by friend Eon McKai as a sneak peek from a film he’s currently working on called “On My Dirty Knees”.

There are a lot of interesting points in this piece about the so-called “frigid woman” and it’s worth a read; though I’ll warn you it ends on a stupid sexist note. But Tim Cavanaugh hits home in When Free Love Died as he asks a question that is oft-repeated on these pages — why does the cutting edge of erotica feel like it’s still in the past? Here’s a snip from the middle, the juicy bits:

(…) Then suddenly, suspiciously close to the time that the sexual revolution peaked, the Frigid Woman just vanished. Along with nymphomania and the virgin/whore complex, her disease no longer existed, another relic rom the ungroovy dark ages. Was she cured by the no-strings, gettin’-down, good-vibrating, out-front love fest of the late ’60s and early ’70s? Or did she cure herself by fighting off the open-shirted horn dog males unleashed by the Summer of Love?

Two recent entertainments try to recreate the complexity of that era of self-conscious sexual liberation. The CBS series Swingtown attempts to bring ’70s suburban wife swapping to mainstream television. On a much smaller budget, Anna Biller’s independent film Viva salutes classic soft-core cinema. Neither could be accused of making a big cultural splash. Swingtown, largely unwatched, appears headed for cancellation; Viva, despite its uncannily precise rendition of the look, sound, mood, and arch dialogue of its subject, made just a few film festival and theatrical appearances and earned mixed reviews.

But the relative daring of both pieces raises a question: In a world where amputee and plush-toy porn is as near as your Web browser, why does the cutting edge of fictionalized erotic exploration seem to be found on material that’s more than three decades old?

Maybe it’s simple style envy. Swingtown luxuriates in the Super ’70s vibe to a degree that’s bracing even after years of Me Decade nostalgia. Who (other than Nielsen viewers, apparently) could say no to the milieu of plaited hair, randy airline pilots, swinger parties, and paneled kitchens? Viva aims not for the look of the period but for the look of the period’s movies: the high-key, pseudo-Technicolor lighting and spare, colorful set design that a handful of us have been missing ever since Dragnet went off the air; nudge-nudge, wink-wink dialogue delivered in the flattest possible tones; characters who always have a cocktail in one hand and a cigarette in the other.

What both capture is a sense of the sexual revolution as a product of middle age, a phenomenon not strictly of the baby boomers but of people just a few years older, still young enough to grok the counterculture but too old to commit to it in earnest. There is something exquisite in that dilemma. Sure, we’ve all been plagued by the sense that somebody somewhere is getting laid in ecstatic new ways while we’re slaving over a hot stove. But suburbanites in the early ’70s had actual reason to believe it.

That is why the Frigid Woman is the key to this mystery, the explanation for why the sexual revolution contained both new vistas of freedom and the seeds of its own undoing. All that loosening up ultimately contained just more male insistence, a sense that the real problem with society was that women just weren’t putting out enough! The journey to sexual liberation was sold as a step forward for women, but it was also a clever way to eliminate the option of saying no. And while “frigidity” was a phenomenon that had been discussed for decades, it reached critical mass just when the promise of balling your way through to the other side began to seem believable. It turned out women weren’t having a problem achieving orgasm at all; they just couldn’t do it with you.

What’s left of that heady experience? You could say the journey has been completed in the Housewives and the City entertainment genre of sexually liberated women. You can find the evidence all over the bestseller lists—novels full of breathless detail about Manolo shoes, Pilatestoned figures, fiery redheads, cussing bitches with hearts of gold, lovel Korean-American gal pals, arrogant but sexy assholes, and giggly revelations over white wines. (…read more! thanks Praemedia!)

My view? Seventies sex was exotic. It was transgressive. It was modern. It was fun. It was after Roe, but before the Great Plague , i.e.- the consequences were manageable. By the time I and my peers attained our majority, sex had become at once more fearful, and yet at the same time more commonplace, tolerated less, like with pot before it, ‘just say no’ overthrew ‘just say o’.

And today? Anything goes. We have become relatively desensitized, sex has lost some of its mystery. Despite how bleak it sounds, this is far from all bad. Quality has begun to overtake quantity in our sex lives, more ‘relationship sex’, less frantic, fearful coupling. It means we have an interest in being better rather than bigger lovers. It means Violet Blue’s message is getting through. Thank you!

IMHO, “frigid” women were lesbian women compelled by social pressure into marriages with men to whom they weren’t the least bit attracted. It wasn’t the sexual revolution that obliterated the frigid woman, it was the feminist revolution, or perhaps gay liberation.

(I don’t quite understand how anything that can pass muster with the CBS Standards & Practices office can also be at the cutting edge of erotic exploration.)